Junglepixiebelize - Recollections of a Gringa Pioneer

Nancy R Koerner - Copyright@2021 - All Rights Reserved

CHAPTER ONE

"Midnight Arrival - 1976"

“If the world had any ends,” Aldous Huxley wrote in 1934, “British Honduras would certainly be one of them. It is not on the way from anywhere, to anywhere else.” So true. In those days, forty-five years ago, there were not even any maps of Belize. When I had gone to a U.S. library, in a desperate attempt to find a reference for “our trip to nowhere."I realized Aldous Huxley was right. There was only one road into Belize from Mexico, and then a mere pretense of two or three faint lines that dawdled westward and southward before petering out completely. Laying open that giant Encyclopedia Britannica, I used my flimsy piece of tracing paper and pencil to reproduce the hand-drawn map which would end up being our one-and-only guide into a brand new life.

Now we were on that very same road, heading south from Chetumal. The paved road was bordered on either side by open flat desolate scrub land. But straight ahead? Nothing but darkness ahead. Darkness. That was putting it mildly. Jet black. Dark as outer space. Dark as a tomb. Dark as death. No faraway glow of a city, or town. Not even a flicker from the fire hearth of a distant villager. Suddenly, the hum of civilized Mexican asphalt disintegrated into the harsh rumble of a stony, potholed, washboard dirt track. The abrupt change in road surface coincided with the appearance of a tiny bare-wood, hand-painted sign on the right side of the road. It was about a foot off the ground. Perhaps 6” x 18". BELIZE

The tiny tumbledown shack for Immigration and Customs was veiled in darkness, except for a feeble beam of light shining through the gaps in the rickety wallboards. We parked (anywhere) and approached the open door of the building. The source of light turned out to be a single naked lightbulb, dangling from a bare electrical wire in the ceiling. Inside, the room was so dim it was almost impossible to make out the forms of the two very dark-skinned men behind the counter. They mumbled to each other in some incomprehensible dialect, as they fiddled with the cheap transistor radio.

"Look hyah, bwai. Dis ting no work correc ah tall," said the shorter man, as he twisted the knobs. "Bwai," replied the taller one, "Da yu, fool-fool. No di radio. Yu no kno noting bout how di bloody ting funkshun propah.

Excuse me? Is this Immigration and Customs?"

(Looking up.) "I da di Immigrashun. He da di Customs. (Suddenly, business-like.) Mek Ah see fu yu paypahs."

If it had been difficult to going through Mexico without speaking Spanish, it was much worse in Belize because we knew they were speaking English. Yet we couldn’t understand a word. Asking a border official to repeat himself was useless. An unintelligible word spoken more slowly, was just as unintelligible. Many questions. Why were we here? How long? Where would we stay? Who did we know? How much money did we have? What we were bringing in? TVs, guns? Watches, metal detectors? Tools? Alcohol, illegal drugs? Luckily, the U.S. five dollar bill my husband produced for each man suddenly smoothed things over as beautifully as the Mexican pavement we’d just left behind. Good. At least, in that respect, Belize appeared to be a very civilized country.

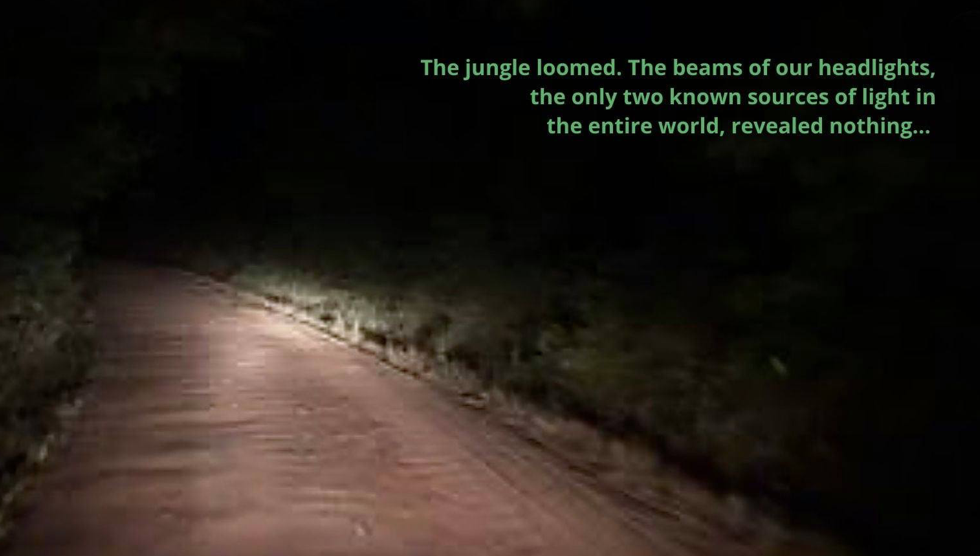

So, at 1:30AM, on January 20th, 1976, our little family of three – father, mother, and nine-month old baby – driving an old beat-up modified ’59 Ford step-van, with only a couple of thousand U.S. to our names – which would theoretically have to last us the rest of our lives – gained entry into the land of promise. But, as the tiny tumbledown shack disappeared in the rearview mirror, the walls closed in. Triple canopied jungle choked the already-narrow dirt track. After a few more miles in the consummate blackness, our adrenaline now spent, we desperately needed to pull off the road and sleep. Easier said than done. From the beams of our headlights – seemingly the only two known sources of light in the entire world – the road, if you could call it that, had barely enough room for two opposing vehicles to pass. The old van trundled along for another hour before we found a spot to pull over, still marginal at best.

Anxiety troubled me as I lay in the airless van, sleepless, beside my husband and baby. Outside, mosquitoes buzzing, there was no evidence of human habitation. None whatsoever. Not a sign, not a fence, not a house. Still not a streetlight, not a lamppost, still no glow of a distant city, or village, not even a distant fire in some primitive hearth. There was no breeze. The black jungle still loomed tightly on both sides of the narrow road. This wasn’t another country; this was another planet.

Of course, I could not have then imagined all the light-and-life that would lie ahead: the charm and bustle of Belize City, the Swing Bridge and Ramsey’s mule, of meat pies and conch fritters, of Lord Rhaburn and the Boom-n-Chime Band. I had not yet seen the sparkle of sunlight on the sea, nor yet listened to Seferino Coleman on Radio Belize praise “this beautiful little jewel of ours” as he played Morning Dance by Spyro Gyra. Yes, all of this would be in the future. But not yet.

Instead, for this moment, the surrounding darkness was all-pervasive. The black night outside the van was so complete, the perfect stillness so absolute, and the air so sultry, I felt we’d entered the interior of darkest Africa in a past century. My last thought, as I finally drifted into sleep, was “Dr. Livingston, I presume?”

The tiny tumbledown shack for Immigration and Customs was veiled in darkness, except for a feeble beam of light shining through the gaps in the rickety wallboards. We parked (anywhere) and approached the open door of the building. The source of light turned out to be a single naked lightbulb, dangling from a bare electrical wire in the ceiling. Inside, the room was so dim it was almost impossible to make out the forms of the two very dark-skinned men behind the counter. They mumbled to each other in some incomprehensible dialect, as they fiddled with the cheap transistor radio.

"Look hyah, bwai. Dis ting no work correc ah tall," said the shorter man, as he twisted the knobs. "Bwai," replied the taller one, "Da yu, fool-fool. No di radio. Yu no kno noting bout how di bloody ting funkshun propah.

Excuse me? Is this Immigration and Customs?"

(Looking up.) "I da di Immigrashun. He da di Customs. (Suddenly, business-like.) Mek Ah see fu yu paypahs."

If it had been difficult to going through Mexico without speaking Spanish, it was much worse in Belize because we knew they were speaking English. Yet we couldn’t understand a word. Asking a border official to repeat himself was useless. An unintelligible word spoken more slowly, was just as unintelligible. Many questions. Why were we here? How long? Where would we stay? Who did we know? How much money did we have? What we were bringing in? TVs, guns? Watches, metal detectors? Tools? Alcohol, illegal drugs? Luckily, the U.S. five dollar bill my husband produced for each man suddenly smoothed things over as beautifully as the Mexican pavement we’d just left behind. Good. At least, in that respect, Belize appeared to be a very civilized country.

So, at 1:30AM, on January 20th, 1976, our little family of three – father, mother, and nine-month old baby – driving an old beat-up modified ’59 Ford step-van, with only a couple of thousand U.S. to our names – which would theoretically have to last us the rest of our lives – gained entry into the land of promise. But, as the tiny tumbledown shack disappeared in the rearview mirror, the walls closed in. Triple canopied jungle choked the already-narrow dirt track. After a few more miles in the consummate blackness, our adrenaline now spent, we desperately needed to pull off the road and sleep. Easier said than done. From the beams of our headlights – seemingly the only two known sources of light in the entire world – the road, if you could call it that, had barely enough room for two opposing vehicles to pass. The old van trundled along for another hour before we found a spot to pull over, still marginal at best.

Anxiety troubled me as I lay in the airless van, sleepless, beside my husband and baby. Outside, mosquitoes buzzing, there was no evidence of human habitation. None whatsoever. Not a sign, not a fence, not a house. Still not a streetlight, not a lamppost, still no glow of a distant city, or village, not even a distant fire in some primitive hearth. There was no breeze. The black jungle still loomed tightly on both sides of the narrow road. This wasn’t another country; this was another planet.

Of course, I could not have then imagined all the light-and-life that would lie ahead: the charm and bustle of Belize City, the Swing Bridge and Ramsey’s mule, of meat pies and conch fritters, of Lord Rhaburn and the Boom-n-Chime Band. I had not yet seen the sparkle of sunlight on the sea, nor yet listened to Seferino Coleman on Radio Belize praise “this beautiful little jewel of ours” as he played Morning Dance by Spyro Gyra. Yes, all of this would be in the future. But not yet.

Instead, for this moment, the surrounding darkness was all-pervasive. The black night outside the van was so complete, the perfect stillness so absolute, and the air so sultry, I felt we’d entered the interior of darkest Africa in a past century. My last thought, as I finally drifted into sleep, was “Dr. Livingston, I presume?”