Junglepixiebelize - Recollections of a Gringa Pioneer

Nancy R Koerner - Copyright@2021 - All Rights Reserved

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

"Escandar Bedran - El Padrino"

|

When immigrants from the Mount Lebanon area of the Middle East (then called “Greater Syria”) arrived in Belize in the early 1900’s, they were referred to as “Turks,” or “Turcos” in Spanish, an expression that still lingers today. But they were not Turkish, did not speak Turkish, and the Ottoman Empire had been their oppressors. This first generation had apparently arrived with little more than clothes they wore, but they were a smart and resourceful people. In San Ignacio, these are the names we still know today: Awe, Habet, Zaiden, Espat, Chebat, and Bedran.

I’d come to town on the dory with Dicky Simpson that Saturday morning, not just for marketing, but for a bit of advice too. We had been in Belize for three months of a six-month visitor’s permit, but already knew we wanted to stay. We needed a permanent solution, and everybody had given me the same advice. Escandar Bedran was the most influential businessman in all Cayo. He knew everybody, had all the answers, and was building a hotel up on the hill. He was “El Padrino,” and apparently, “godfather to half of Cayo.” |

Standing there in front of the Police Station, I stared up the of Buena Vista Street, thinking it was about the same as climbing the ruins of Xunantunich. My mother had sent me a baby back-pack from the States, which was a godsend. But my son was now a full-year-old and weighed the same as two bowling balls. And my feet were still my only wheels. Geez, it was a steep freaking hill.

Huffing, puffing, and sweating, I arrived at the top, and got my first look at the new hotel under construction. The sunshine was bright-white. Piles of cinderblock were stacked by the entrance, beyond which I saw a cloud of cement dust rise and hover briefly before being whisked away on the dry-season breeze. I ducked in the door, closing the umbrella I’d used to shade my baby, made my request to the young lady at the reception desk, and she went off to find her Tio Escandar.

A few minutes later, a short jovial man with a round face came forward, smiling, his hand extended in courtesy. I expressed my gratitude that he would meet with me. Back-lit and silhouetted by the sunshine outdoors, it took a minute before he saw the corn-haired baby on my back, and the man melted like "wa Ideal inna di sun-haat." Escandar Bedran loved babies. He should. He had seven of them. He invited me to join him at the bar, and we ended up sitting in easy conversation over a couple of Cokes for the better part of an hour. Bouncing my baby on his knee, Escandar asked how we were enjoying life in Belize, and what we hoped to achieve. I told him we wanted to stay, buy land, that were looking for advice on permanent status. He nodded thoughtfully, and then began to tell me something of his own history.

In the old country, Escandar’s ancestors had been peddlers. When the Lebanese had landed in Belize and migrated the Cayo District, this penchant for trade fit perfectly with the needs of the chicle and logging industries. As encargaderos, they acted as brokers in the chain of supply-and-demand. The Cayo boats carried the blocks of raw chicle downstream to Belize City, a journey of two days. Then it took a full three weeks to bring goods-for-sale, back upstream, against the current. Once delivered to the savannah, they had used mules, or packed the goods-for-sale on their backs and walked to the isolated camps in the high-bush, carrying clothing, soaps, liquor, tobacco products, and other dry goods for the loggers and chicleros.

Escandar told me that he, himself, as a boy, had pushed a small cart, selling milk in the streets of San Ignacio. Later, as a young man, he had worked alongside his Uncle Emilio Awe, in both logging and chicle. As the tenacious Lebanese people prospered, they came to own and operate small family businesses – groceries, dry goods, and bars – eventually dominating the mercantile sector of Cayo.

As our conversation drew to a close, Escandar smiled, and spoke kindly. He was going to contact Belmopan, and arrange to waive the $500 bond that would normally be required for permanent visas. He was going to personally “sponsor” our young family. Astonished, I asked why he would do that? He told me that the very fact I’d walked up that enormous hill, carrying a heavy baby on my back, in the hot sun, had showed my toughness and resolve – that he’d recognized the same pioneer spirit of his people. Overwhelmed with gratitude, I hugged him impulsively, and thanked him profusely. He waved me off, and ruffled my son’s blond hair. “Besides” he said, “I like dis lee bwai – wit’ fu-hihn big coc’nut hed.”

Huffing, puffing, and sweating, I arrived at the top, and got my first look at the new hotel under construction. The sunshine was bright-white. Piles of cinderblock were stacked by the entrance, beyond which I saw a cloud of cement dust rise and hover briefly before being whisked away on the dry-season breeze. I ducked in the door, closing the umbrella I’d used to shade my baby, made my request to the young lady at the reception desk, and she went off to find her Tio Escandar.

A few minutes later, a short jovial man with a round face came forward, smiling, his hand extended in courtesy. I expressed my gratitude that he would meet with me. Back-lit and silhouetted by the sunshine outdoors, it took a minute before he saw the corn-haired baby on my back, and the man melted like "wa Ideal inna di sun-haat." Escandar Bedran loved babies. He should. He had seven of them. He invited me to join him at the bar, and we ended up sitting in easy conversation over a couple of Cokes for the better part of an hour. Bouncing my baby on his knee, Escandar asked how we were enjoying life in Belize, and what we hoped to achieve. I told him we wanted to stay, buy land, that were looking for advice on permanent status. He nodded thoughtfully, and then began to tell me something of his own history.

In the old country, Escandar’s ancestors had been peddlers. When the Lebanese had landed in Belize and migrated the Cayo District, this penchant for trade fit perfectly with the needs of the chicle and logging industries. As encargaderos, they acted as brokers in the chain of supply-and-demand. The Cayo boats carried the blocks of raw chicle downstream to Belize City, a journey of two days. Then it took a full three weeks to bring goods-for-sale, back upstream, against the current. Once delivered to the savannah, they had used mules, or packed the goods-for-sale on their backs and walked to the isolated camps in the high-bush, carrying clothing, soaps, liquor, tobacco products, and other dry goods for the loggers and chicleros.

Escandar told me that he, himself, as a boy, had pushed a small cart, selling milk in the streets of San Ignacio. Later, as a young man, he had worked alongside his Uncle Emilio Awe, in both logging and chicle. As the tenacious Lebanese people prospered, they came to own and operate small family businesses – groceries, dry goods, and bars – eventually dominating the mercantile sector of Cayo.

As our conversation drew to a close, Escandar smiled, and spoke kindly. He was going to contact Belmopan, and arrange to waive the $500 bond that would normally be required for permanent visas. He was going to personally “sponsor” our young family. Astonished, I asked why he would do that? He told me that the very fact I’d walked up that enormous hill, carrying a heavy baby on my back, in the hot sun, had showed my toughness and resolve – that he’d recognized the same pioneer spirit of his people. Overwhelmed with gratitude, I hugged him impulsively, and thanked him profusely. He waved me off, and ruffled my son’s blond hair. “Besides” he said, “I like dis lee bwai – wit’ fu-hihn big coc’nut hed.”

|

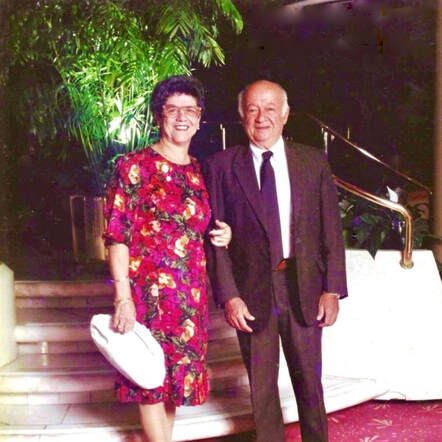

I want to honour Escandar Bedran and express my gratitude for the man who helped us get a fair start, and who “wanted to do something nice for the people of Cayo.” The building of the San Ignacio Hotel had begun ten years before the first inklings of tourism, a testament to the man’s talent and vision. As the place thrived and grew, so did my friendship with Escandar, his wife, Paulita, his children, and extended family.

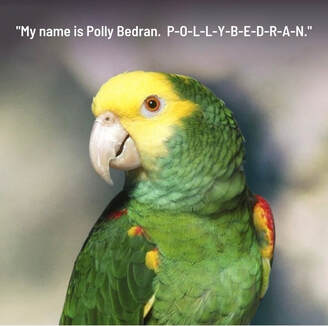

I even got to know the family parrot – a talented yellow-head named “Polly Bedran,” who, thanks to Dona Paulita, could spell his own name, call out the names of all the children – Teresita, Abdallah, Nazle, Mariam, Escandar, Amin, Paulita – as well as sing ALL the words to “I Don’t Know Why I Love You Like I Do,” “Happy Birthday to You” and “Yankee Doodle,” all in perfect Kriol. |