Junglepixiebelize - Recollections of a Gringa Pioneer

Nancy R Koerner - Copyright@2021 - All Rights Reserved

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

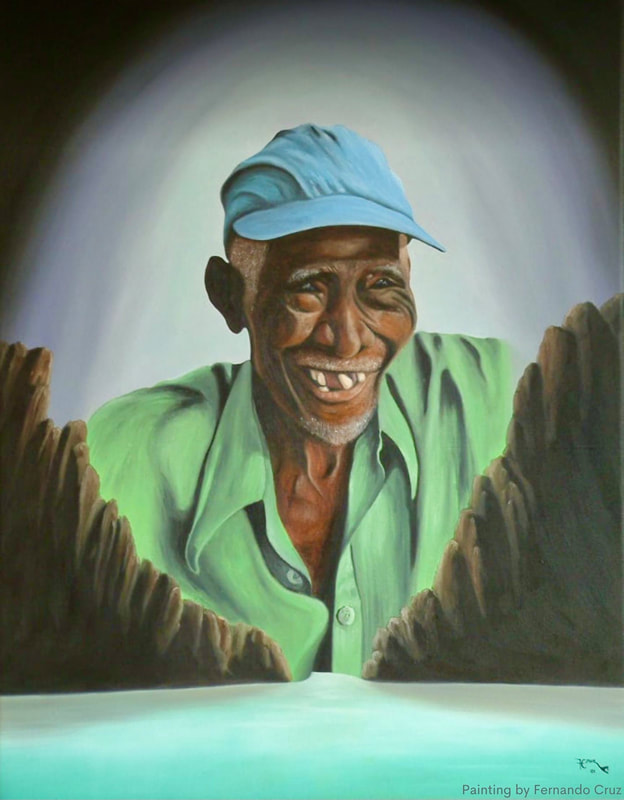

"Old Thomas Green of Big Eddy"

|

A number of colourful characters inhabited the Macal Valley in those days. Across the river, on the west side, and just upstream, Old Victor Tut lived in a tiny thatched house with his wife, Dona Felipa. They would catch little sardines in the river, roast them whole, and wrap them in corn tortilla, or the (sassafras-like) leaf of the obel. The old Maya man enjoyed his strong rum, and would sometimes walk the river bank shouting at the top of his voice. "Reatta en la vida," he would say, tapping himself on the chest. "Me lovin'. Me good." The nickname stuck. Old Reatta was caretaker for the Englishman, Jack Garden, who would soon sell the property to Mick and Lucy Fleming. It would later become the Chaa Creek Cottages, and eventually the famous Chaa Creek River Lodge.

On the eastern side, where we lived, our neighbour immediately downstream, was Victorito Tut and his wife TeresitaGreen. Further upstream, her parents, Thomas and Teresa Green owned the property called Big Eddy. From Macaw Bank to San Ignacio, it was the single most-picturesque location on the river, and the magnificent bend also held its deepest waters. The emerald-green pool was studded with two enormous free-standing towers of rock, each bigger than a house, which soared thirty feet above the waterline, and sank another twenty below. |

In dry season, the water was so clear, so glassy-green, you could see all the way to the rock-base, and catch a glimpse of a monster tarpon, as much as nine feet long, hiding in the shadows. Besides his property at Big Eddy, also owned a piece of farmland on Benque Road, between San Jose Succotz and San Ignacio, near Figueroa’s farm, where he grew vegetables during the week. While staying on the ranch, he would ride his bicycle to San Ignacio, and then bring fresh veggies back to the river on weekends. He was also a practiced herbalist, and drank fever-grass tea every day of his life.

Of all the river men Old Thomas was perhaps the most iconic. Tall, spare, and lanky, he always wore a baseball cap on his close-cropped snowy head. Thomas had few remaining teeth – all of them askew – and easily visible, because he was always smiling. Thomas had a quiet, almost mischievous, sense of humour, and his chocolate eyes had a way of crinkling at the corners. It was as though he knew the “secret of life,” and most of that secret was about laughter. He was a soft-spoken, peaceful man, and those who knew him best would attest that, in his entire life, they’d never seen him “get vex.” With his wife Teresa, Thomas had fathered two children: Teresita and Chico (Francisco), plus four step-children, thirteen biological grandchildren, and thirty-eight step-grandchildren. Unknown to many, he had actually served in Germany in WW2, and had returned from the war owning a couple of wool coats. His wife had cut them up and made them into a blanket for chilly January nights.

Thomas Green was an expert dory builder, and absolute virtuoso in navigating the Macal. In smooth deep water, he paddled a perfect j-stroke, directionally stable by definition, never needing to switch sides to correct his course. In the shallower waters, he would stand up in the stern and switch to a long pole. With this higher center-of-gravity, Thomas would land the foot of the pole about half-a-dory-length ahead, expertly placing it among the smooth river stones. Once past the apex of the arc, he would push hard to complete the stroke, the pole ending up far behind the boat. If the river was exceptionally shallow, Thomas would step all the way up on the tip of the stern, balancing his tall, spare body and big feet on that tiny precarious wooden triangle. (It was like watching someone balance a yardstick on the tip of their index finger.) His weight at that far position would serve to elevate the bow, ever-so-slightly, and minimize surface drag. Once a fluid momentum was established, and then using the least amount of energy, he almost seemed to fly. I had often seen him pole the dory over thirty feet upstream in a single stroke. It was grace, personified.

In 1984, Thomas Green received an unlikely invitation to be a part of the Louisiana World Exposition in New Orleans. The Expo wanted him as a live exhibit for the show, using his adze to hew out an authentic river dory, in real time. Thomas had accepted. Receiving VIP treatment, he was flown to New Orleans, along with a giant Belizean mahogany log. The old Creole had had the time of his life: first flying in the airplane, then riding around in fancy cars, staying in fancy hotels, and demonstrating his dory-making skills for thousands upon thousands of international spectators. Thomas had soaked in all the attention, and become the darling of the show. And so it came to pass that a simple Macal riverman, from the Cayo District of Belize, even got to meet U.S. Secretary of State, George Schultz.

Although Thomas Green read his Bible daily, he never belonged to any organized religion. Once the Jehovah Witnesses had invited him to join, along with the caveat that he would, as a matter of course, need to legally marry his common-law wife of over fifty years. To that Thomas Green had replied in mock indignation, “Dat oal gyal? Dat oal gyal? Cho! If I gwine marid, Ah wa marid wa *yong* gyal!” (That old gal? That old gal? If I'm going to marry, I'm going to marry a young gal!)

Of all the river men Old Thomas was perhaps the most iconic. Tall, spare, and lanky, he always wore a baseball cap on his close-cropped snowy head. Thomas had few remaining teeth – all of them askew – and easily visible, because he was always smiling. Thomas had a quiet, almost mischievous, sense of humour, and his chocolate eyes had a way of crinkling at the corners. It was as though he knew the “secret of life,” and most of that secret was about laughter. He was a soft-spoken, peaceful man, and those who knew him best would attest that, in his entire life, they’d never seen him “get vex.” With his wife Teresa, Thomas had fathered two children: Teresita and Chico (Francisco), plus four step-children, thirteen biological grandchildren, and thirty-eight step-grandchildren. Unknown to many, he had actually served in Germany in WW2, and had returned from the war owning a couple of wool coats. His wife had cut them up and made them into a blanket for chilly January nights.

Thomas Green was an expert dory builder, and absolute virtuoso in navigating the Macal. In smooth deep water, he paddled a perfect j-stroke, directionally stable by definition, never needing to switch sides to correct his course. In the shallower waters, he would stand up in the stern and switch to a long pole. With this higher center-of-gravity, Thomas would land the foot of the pole about half-a-dory-length ahead, expertly placing it among the smooth river stones. Once past the apex of the arc, he would push hard to complete the stroke, the pole ending up far behind the boat. If the river was exceptionally shallow, Thomas would step all the way up on the tip of the stern, balancing his tall, spare body and big feet on that tiny precarious wooden triangle. (It was like watching someone balance a yardstick on the tip of their index finger.) His weight at that far position would serve to elevate the bow, ever-so-slightly, and minimize surface drag. Once a fluid momentum was established, and then using the least amount of energy, he almost seemed to fly. I had often seen him pole the dory over thirty feet upstream in a single stroke. It was grace, personified.

In 1984, Thomas Green received an unlikely invitation to be a part of the Louisiana World Exposition in New Orleans. The Expo wanted him as a live exhibit for the show, using his adze to hew out an authentic river dory, in real time. Thomas had accepted. Receiving VIP treatment, he was flown to New Orleans, along with a giant Belizean mahogany log. The old Creole had had the time of his life: first flying in the airplane, then riding around in fancy cars, staying in fancy hotels, and demonstrating his dory-making skills for thousands upon thousands of international spectators. Thomas had soaked in all the attention, and become the darling of the show. And so it came to pass that a simple Macal riverman, from the Cayo District of Belize, even got to meet U.S. Secretary of State, George Schultz.

Although Thomas Green read his Bible daily, he never belonged to any organized religion. Once the Jehovah Witnesses had invited him to join, along with the caveat that he would, as a matter of course, need to legally marry his common-law wife of over fifty years. To that Thomas Green had replied in mock indignation, “Dat oal gyal? Dat oal gyal? Cho! If I gwine marid, Ah wa marid wa *yong* gyal!” (That old gal? That old gal? If I'm going to marry, I'm going to marry a young gal!)