Junglepixiebelize - Recollections of a Gringa Pioneer

Nancy R Koerner - Copyright@2021 - All Rights Reserved

CHAPTER THIRTY

"The Evil Protozoa"

"The Evil Protozoa"

There were risks to life in Belize, of course. All Cayo gringos knew that in advance. There were the colourful movie-inspired risks that might get you, like jaguar attack and snake bite, but highly-unlikely. Then there were things that could get you: hurricane, earthquake, wildfire, or flood. Much more likely, but maybe avoidable. And then there were the things that probably would actually get you, at least, at some point: pink eye, beef worm, poisonwood, and staph infection. And yes, we knew Anophelesmosquitoes carried malaria, that Aedes Aegypti carried dengue, and both species were present in Belize, but we “didn’t think that could happen to us.”

Optimism bias is a cognitive bias that causes someone to believe

that they, themselves, are less likely to experience a negative event.

And yet, looking back over the years, I knew one or two people who had fallen victim to every single misfortune mentioned above. (Yes, jaguar and snake included.) However, none of us had prior knowledge of a nasty little protozoa, carried by certain kind of phlebotomine sand fly, which could cause the ugliest disease I had ever laid eyes on: leishmaniasis. \\

Optimism bias is a cognitive bias that causes someone to believe

that they, themselves, are less likely to experience a negative event.

And yet, looking back over the years, I knew one or two people who had fallen victim to every single misfortune mentioned above. (Yes, jaguar and snake included.) However, none of us had prior knowledge of a nasty little protozoa, carried by certain kind of phlebotomine sand fly, which could cause the ugliest disease I had ever laid eyes on: leishmaniasis. \\

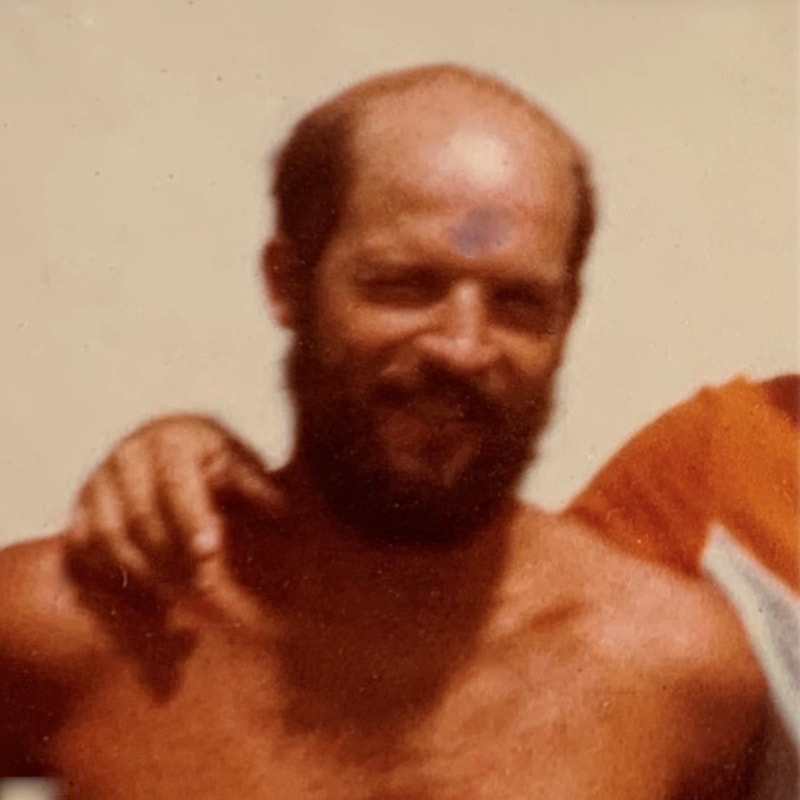

I had met Pat Cartwright in San Ignacio one typical Saturday morning market in the same manner as nearly every other recently-arrived gringo in Cayo. Pat was in his late twenties, lean-muscled, and darkly tanned. He had on a T-shirt, light-weight khaki shorts, and worn a navy bandanna, gypsy-style, over the dome of his prematurely bald head. Pat and his wife, Sharon, were one of three gringo couples living back in upper Barton Creek near the big cave. I liked him immediately. We spoke for a while, then walked over to the ‘panadas stand, and shared some tostados, garnaches, and a couple of cold Cokes. (Yeah, I know. So much for health food freaks, avoiding meat, fried foods, and sugary soft drinks, right?)

Then Pat told me he had to catch a ride to Holdfast Camp, near Central Farm, to see a British Army doctor. He needed to get second round of heavy metal injections for a large wound he had sustained. What? I didn’t understand. What kind of wound needed so radical a treatment? It wouldn’t respond to antibiotics? Pat explained that it had come from the bite of a sand fly, that the protozoan infection had created a huge lesion. Self-consciously, he touched his forehead, gave a resigned gesture, and lifted his bandanna. I flinched. Apparently, leishmaniasis was a flesh-eating disease.

“Holy shit, Pat,“ I said. “You working on your third eye, or what?” I immediately regretted my reckless comment, as well as my look of utter revulsion.

It was wet, shiny, and raw, a red and pink wound, suppurating with white and yellow pus, and punctuated with tiny black scabs. There was a raised ridge of skin around the edge of the oval sore, and it was HUGE – now bigger than a Belize shilling. Starting out as a mere dot, it had grown quickly and exponentially. No treatment had been successful in actually curing it, although the first round of heavy metal injections had seemed to arrest any further spread. Worse yet, the shots were cutaneous, and local, injected directly into his forehead around the entire circumference of the wound.

Thankfully, I never got leishmaniasis, and neither did any of my family. But one of my other gringa girlfriends in Barton Creek acquired two even-larger wounds on the back of her left calf, and another gringo friend of mine in the Mountain Pine Ridge developed a lesion of nearly the same size on the back of his right hand. They, too, had no choice but to submit to the heavy metal injection treatments, and thankfully, all were eventually cured. *Eventually* being the operative word. But the vicious scars remained.

Luckily, nowadays, there are modern alternatives to treat leishmaniasis. But, at the time, in 1976, considering the severity of both the disease and the cure, the best course of action was to NOT get bitten in the first place. (A rough read, I know, but it’s Belizean HISTORY.)

Then Pat told me he had to catch a ride to Holdfast Camp, near Central Farm, to see a British Army doctor. He needed to get second round of heavy metal injections for a large wound he had sustained. What? I didn’t understand. What kind of wound needed so radical a treatment? It wouldn’t respond to antibiotics? Pat explained that it had come from the bite of a sand fly, that the protozoan infection had created a huge lesion. Self-consciously, he touched his forehead, gave a resigned gesture, and lifted his bandanna. I flinched. Apparently, leishmaniasis was a flesh-eating disease.

“Holy shit, Pat,“ I said. “You working on your third eye, or what?” I immediately regretted my reckless comment, as well as my look of utter revulsion.

It was wet, shiny, and raw, a red and pink wound, suppurating with white and yellow pus, and punctuated with tiny black scabs. There was a raised ridge of skin around the edge of the oval sore, and it was HUGE – now bigger than a Belize shilling. Starting out as a mere dot, it had grown quickly and exponentially. No treatment had been successful in actually curing it, although the first round of heavy metal injections had seemed to arrest any further spread. Worse yet, the shots were cutaneous, and local, injected directly into his forehead around the entire circumference of the wound.

Thankfully, I never got leishmaniasis, and neither did any of my family. But one of my other gringa girlfriends in Barton Creek acquired two even-larger wounds on the back of her left calf, and another gringo friend of mine in the Mountain Pine Ridge developed a lesion of nearly the same size on the back of his right hand. They, too, had no choice but to submit to the heavy metal injection treatments, and thankfully, all were eventually cured. *Eventually* being the operative word. But the vicious scars remained.

Luckily, nowadays, there are modern alternatives to treat leishmaniasis. But, at the time, in 1976, considering the severity of both the disease and the cure, the best course of action was to NOT get bitten in the first place. (A rough read, I know, but it’s Belizean HISTORY.)