|

(05/15/23)

|

Junglepixiebelize - Recollections of a Gringa Pioneer

Nancy R Koerner - Copyright@2023 - All Rights Reserved

CHAPTER FIFTY-NINE

"Hurricane Greta - Part 3 - Aftermath Mud Wallowing"

Before life in Belize, I had always considered mud to be a superficial substance, a thin coating that might collect on the soles of my boots after walking through a puddle. But I had never truly seen MUD until I moved to Belize.

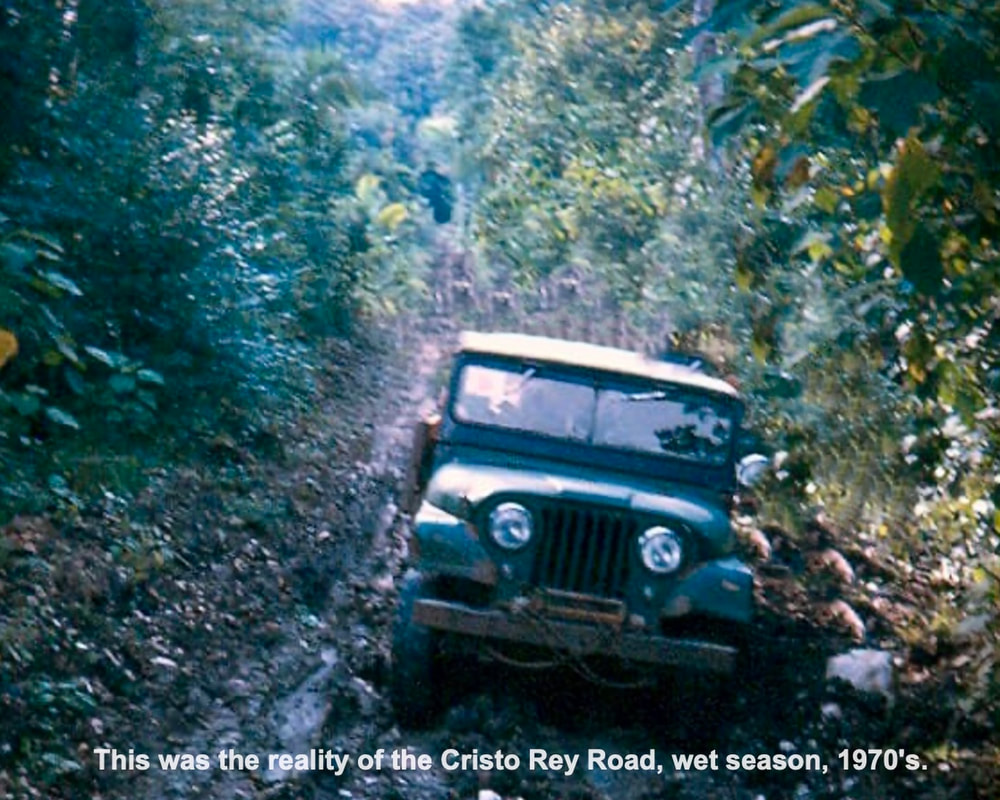

Mud was its own autonomous entity. A mud wallow on the Cristo Rey Road was a physical presence with the breadth, depth, and viscosity to stop you in your tracks. Mud so deep, you could literally break a leg if you did not slow your stride to accommodate its resistance. Mud so deep it would suck the boots right off your feet. So deep it could flow over your boot-tops and fill them. So deep it would suck the iron shoes right off the horse.

Mud was its own autonomous entity. A mud wallow on the Cristo Rey Road was a physical presence with the breadth, depth, and viscosity to stop you in your tracks. Mud so deep, you could literally break a leg if you did not slow your stride to accommodate its resistance. Mud so deep it would suck the boots right off your feet. So deep it could flow over your boot-tops and fill them. So deep it would suck the iron shoes right off the horse.

In the wet season, rain might drizzle, pour, or bucket from the sky. It might be an afternoon shower, a heavy downpour, or a total deluge. A low-pressure system might set in for a week or two. Rain would soak into the earth until the soil could absorb no more. On dirt roads, rainwater did little to interfere with life in the bush, as long as the route remained untraveled. But when Polo Neal’s truck made multiple trips down the Cristo Rey Road, heedless of the rains, a transformation took place. The enormous weight of the truck, with its passengers and cargo, and big knobby tires, ground and chewed up the road, churning water and chunks of earth into a deep near-impassable quagmire.

Some places along the Cristo Rey Road had culverts buried crossways under the road bed to divert water. These were large galvanized corrugated drainage pipes, installed by the PWD at the bottom of valleys with well-established springs. But always, in the rainy season, new springs would unexpectedly gush from the mountainsides and flow into valleys that flowed across the dirt road where there were no culverts. And these were the places that gave birth to mud wallows.

Once there was a huge road grader that got stuck on the stretch between Maya Mountain Lodge and Cristo Rey village, when its right front wheel cracked down through the culvert and dropped into five feet of the red-brown slurry. Heavily tilted, the machine ended up staying right there, as the Public Works Department had nothing bigger with which to pull it out. It was said that when the grader was finally extracted, four months later, the wheel was gone. Not just the tire, mind you, but the entire right front wheel – rim, bolts, lug nuts, tie-rod ends, bearings, and all.

There was a genuine art to driving through mud like this – a technique that was more about aiming and momentum, than about power, or four-wheel-drive – although, you really needed all-of-the-above. Picture the anatomy of a mud wallow on a jungle track in the bush: two parallel wheel ruts of sloppy mud, thicker than cake-batter, and as much as 16” deep. Then there was the raised muddy hump in between, and the comparative higher ground on either side. Surprisingly, the trick was NOT to put the transmission in low-range four-wheel drive, first gear, and grind your way slowly through the ruts. Dumb gringos and greenhorns got to try this stunt exactly once. The differential on the vehicle (the round protruding part of the axle assembly that connects to the transmission through the driveshaft) would inadvertently ground-out on the hump of mud in the middle. And, right there, the gringo would stay – with wheels spinning uselessly in mud and water, unable to make contact with the ground.

Instead, I had learned to put the vehicle into high-range four-wheel drive, second-gear, then get up some speed, and charge at the mud wallow, steering for the high ground on the right, and aiming the left wheels to ride the middle hump. Of course, I didn’t expect to get all the way through before slipping into the ruts. But, with enough momentum, I was able to get almost all the way through before careening and dropping sideways. And, in that moment, I would slam the transmission into low range, and then “turtle” my way out of the last yard or two. And, sure enough, with practice, I got to be pretty good at it.

\

The British soldiers on jungle training were no match for the Cristo Rey Road. As much as we enjoyed their sense of humour, and generous gifts of radio batteries and good Scotch, we still teased them as “Whiteys from Blighty.” Even with powered winches on their Land Rovers, cables that could be fastened around trees to crank them out, they still often failed to free themselves. I always got a kick out of rescuing soldiers. Here I was, a little 5’3” American lassie, 120 pounds soaking-wet, pulling out their Land Rovers with our old beat-up Toyota Land Cruiser. The soldiers were good sports though. They’d thank me afterwards with gifts of biscuits and chocolate, courtesy of Her Majesty, and then wave at me and jibe that, in the bush, it was “always better to have a wench than a winch.”

************

After Hurricane Greta, it took a full twenty-four hours for Radio Belize to come back on the air. Listening to the reports of damage, I realized that we were better off in the bush. At least, we were autonomous, independent of public utilities. Despite the destruction, we had a full tank of rain water, butane for the stove, and plenty of beans and flour. In addition, we now had a windfall of limes, and more avocados than we could possibly use. The only thing to do was sit tight, and eat bean burritos with guacamole until the rest of the country had a chance to recover. Our isolation would last for three weeks. Only then would we be able to travel down the Cristo Rey Road – through all the aforementioned mud – to get to Cayo. It would be six weeks before my husband could go to Belize City to get his two front teeth repaired.

In San Ignacio Town, the flooding had been horrendous. The Macal had risen so high that the torrent had only been ten feet below the Hawkesworth Bridge. The river had covered the entire savannah, and rushed through the lower stories of houses and shops all along of Burns Avenue. Kalim Habet’s shop was inundated with nine feet of water – a fact that would later be proven by the high water mark left on an interior wall. Figueroa’s on Benque Road, and other general stores on higher ground, ran out of dry goods and staple foods immediately. Across backyards, and into the outhouse pits, the flow of water had now been contaminated with sewage and the bodies of dead animals. Power failure was widespread. Families huddled around candles in the darkness at night. Fresh fruits and vegetables were non-existent, as farmers found themselves not only with damaged crops, but no ability to transport anything from outlying villages.

Some places along the Cristo Rey Road had culverts buried crossways under the road bed to divert water. These were large galvanized corrugated drainage pipes, installed by the PWD at the bottom of valleys with well-established springs. But always, in the rainy season, new springs would unexpectedly gush from the mountainsides and flow into valleys that flowed across the dirt road where there were no culverts. And these were the places that gave birth to mud wallows.

Once there was a huge road grader that got stuck on the stretch between Maya Mountain Lodge and Cristo Rey village, when its right front wheel cracked down through the culvert and dropped into five feet of the red-brown slurry. Heavily tilted, the machine ended up staying right there, as the Public Works Department had nothing bigger with which to pull it out. It was said that when the grader was finally extracted, four months later, the wheel was gone. Not just the tire, mind you, but the entire right front wheel – rim, bolts, lug nuts, tie-rod ends, bearings, and all.

There was a genuine art to driving through mud like this – a technique that was more about aiming and momentum, than about power, or four-wheel-drive – although, you really needed all-of-the-above. Picture the anatomy of a mud wallow on a jungle track in the bush: two parallel wheel ruts of sloppy mud, thicker than cake-batter, and as much as 16” deep. Then there was the raised muddy hump in between, and the comparative higher ground on either side. Surprisingly, the trick was NOT to put the transmission in low-range four-wheel drive, first gear, and grind your way slowly through the ruts. Dumb gringos and greenhorns got to try this stunt exactly once. The differential on the vehicle (the round protruding part of the axle assembly that connects to the transmission through the driveshaft) would inadvertently ground-out on the hump of mud in the middle. And, right there, the gringo would stay – with wheels spinning uselessly in mud and water, unable to make contact with the ground.

Instead, I had learned to put the vehicle into high-range four-wheel drive, second-gear, then get up some speed, and charge at the mud wallow, steering for the high ground on the right, and aiming the left wheels to ride the middle hump. Of course, I didn’t expect to get all the way through before slipping into the ruts. But, with enough momentum, I was able to get almost all the way through before careening and dropping sideways. And, in that moment, I would slam the transmission into low range, and then “turtle” my way out of the last yard or two. And, sure enough, with practice, I got to be pretty good at it.

\

The British soldiers on jungle training were no match for the Cristo Rey Road. As much as we enjoyed their sense of humour, and generous gifts of radio batteries and good Scotch, we still teased them as “Whiteys from Blighty.” Even with powered winches on their Land Rovers, cables that could be fastened around trees to crank them out, they still often failed to free themselves. I always got a kick out of rescuing soldiers. Here I was, a little 5’3” American lassie, 120 pounds soaking-wet, pulling out their Land Rovers with our old beat-up Toyota Land Cruiser. The soldiers were good sports though. They’d thank me afterwards with gifts of biscuits and chocolate, courtesy of Her Majesty, and then wave at me and jibe that, in the bush, it was “always better to have a wench than a winch.”

************

After Hurricane Greta, it took a full twenty-four hours for Radio Belize to come back on the air. Listening to the reports of damage, I realized that we were better off in the bush. At least, we were autonomous, independent of public utilities. Despite the destruction, we had a full tank of rain water, butane for the stove, and plenty of beans and flour. In addition, we now had a windfall of limes, and more avocados than we could possibly use. The only thing to do was sit tight, and eat bean burritos with guacamole until the rest of the country had a chance to recover. Our isolation would last for three weeks. Only then would we be able to travel down the Cristo Rey Road – through all the aforementioned mud – to get to Cayo. It would be six weeks before my husband could go to Belize City to get his two front teeth repaired.

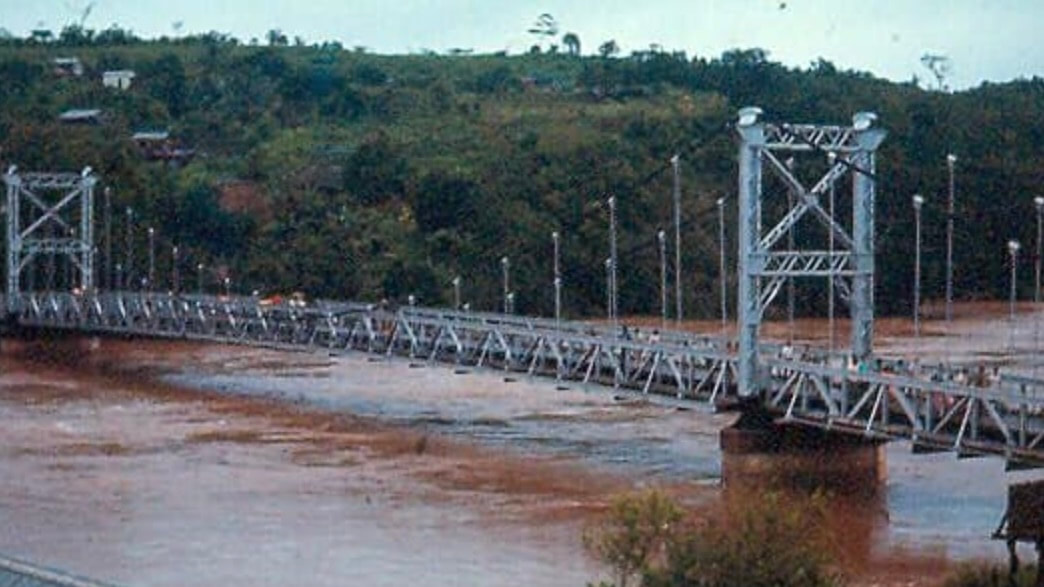

In San Ignacio Town, the flooding had been horrendous. The Macal had risen so high that the torrent had only been ten feet below the Hawkesworth Bridge. The river had covered the entire savannah, and rushed through the lower stories of houses and shops all along of Burns Avenue. Kalim Habet’s shop was inundated with nine feet of water – a fact that would later be proven by the high water mark left on an interior wall. Figueroa’s on Benque Road, and other general stores on higher ground, ran out of dry goods and staple foods immediately. Across backyards, and into the outhouse pits, the flow of water had now been contaminated with sewage and the bodies of dead animals. Power failure was widespread. Families huddled around candles in the darkness at night. Fresh fruits and vegetables were non-existent, as farmers found themselves not only with damaged crops, but no ability to transport anything from outlying villages.

Meanwhile, on the east coast, Hurricane Greta had created havoc in low-lying Belize City. Tanya Russ, who was serving asU.S. Consulate at the time, told me the following story when we met for lunch several months later:

This guy from Corozal comes into the Consulate – the very next day after the hurricane. Several of my staff had told him I wasn’t available, as I was literally dealing with both “hell-and-high-water.” But this guy makes a fuss, still wanting to get his VISA. So, finally, I come out in person. “Hey, have some respect, man. In case you haven’t noticed, we’ve just had a hurricane.” But this guy retorts, “Well, we didn’t have hurricane in Corozal, and besides, the sign on your door still says OPEN.”

“Look, you moron, we’ve got demolished buildings, huge trees torn out by their roots, broken wreckage all over the city, and no electricity. We’ve got a vile four-inch stinking carpet of saltwater mud here inside the Embassy – and YOU want to talk to ME about going to the States? Gimme your name and address. And I’ll make sure you NEVER get a VISA!”

This guy from Corozal comes into the Consulate – the very next day after the hurricane. Several of my staff had told him I wasn’t available, as I was literally dealing with both “hell-and-high-water.” But this guy makes a fuss, still wanting to get his VISA. So, finally, I come out in person. “Hey, have some respect, man. In case you haven’t noticed, we’ve just had a hurricane.” But this guy retorts, “Well, we didn’t have hurricane in Corozal, and besides, the sign on your door still says OPEN.”

“Look, you moron, we’ve got demolished buildings, huge trees torn out by their roots, broken wreckage all over the city, and no electricity. We’ve got a vile four-inch stinking carpet of saltwater mud here inside the Embassy – and YOU want to talk to ME about going to the States? Gimme your name and address. And I’ll make sure you NEVER get a VISA!”